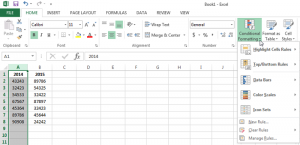

In case we want to do it in a case sensitive way, the following formula would do: = NOT(EXACT(A1,F1))ĮXACT takes two arguments. 🙂Īt this point, you may notice that the formula we used in the above example is case insensitive. We just need to pay attention to where we put the $. When you get this clear, using formula in conditional formatting is secret no more. In H10, whether C10 H10, which is FALSE => not formatted This image illustrates why H2 is highlighted Until it checks the last cell in the range, i.e. In H2, it checks if C2H2, which is TRUE => formatted In H1, it checks if C1 H1, which is FALSE => not formatted In G1, it checks if B1 G1, which is FALSE => not formatted In F1, it checks if A1 F1, which is FALSE => not formatted Since both A1 and F1 are relative, it moves across and down with the active cell. Imagine this, for the range F1:H10 there are invisible formulas behind the scenes to determine if a cell should be formatted or not. It would be easier to “visualize” it indeed: In plain English, these rules ask Excel to look into the range of F1:H10, compare the corresponding cell value in the range starting from A1, cell by cell, then highlight the differences (this is where the formula =A1F1 plays the role).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)